BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN once sang about “going on the town now looking for easy money”. As easy money goes, it is hard to beat farm subsidies. Handouts for American farmers were a tasty $256 billion between 1995 and 2012. The fattest subsidies went to the richest farmers. According to a study by Tom Coburn, a fiscally conservative senator, these have included Mr Springsteen himself, who leases land to an organic farmer. And Jon Bon Jovi, another rocker, paid property taxes of only $100 on an estate where he raises bees. Taxpayers will be glad to know he is no longer “livin’ on a prayer”.

Every five years, Congress mulls a new farm bill. To confuse matters and gin up more votes, the bills typically address two entirely separate problems: the plight of the poor (to whom the federal government gives food stamps) and the unpredictability of farming (which the government seeks to alleviate). Politicians from rural states, which are grotesquely over-represented in the Senate, back farm bills for obvious reasons. Many urban politicians back them, too, not least because some of their constituents depend on food stamps. This time, unusually, the farm bill faces a fight.It will cost around $950 billion over a decade, says the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO). That’s plenty of potatoes to squabble over. Republicans complain that claiming food stamps has become too easy under President Barack Obama—the number of claimants has risen from 26.3m in 2007 to 47.6m today. They want to trim the programme from $760 billion to around $740 billion over ten years. Democrats retort that the rolls have swollen because the economy is in the doldrums. They insist that food stamps are a vital safety net for the poor and do not want them cut.

Oink, oink

Handouts to farmers may also be vulnerable. Proponents of the new bill (of which there are two draft versions) boast that it ends “direct payments” to farmers. These are the subsidies paid to producers of wheat, corn, cotton, rice, peanuts, etc, regardless of whether they actually grow these crops—or even plant them. Other plums, such as “counter-cyclical payments” (extra handouts when prices are low) are also to be eliminated.

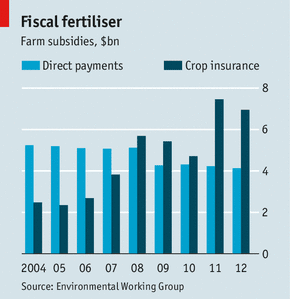

That may sound like a ray of sunshine for taxpayers, but there are clouds looming. Vincent Smith, a professor of farm economics at Montana State University, says the new bill offers a “bait and switch”. Direct payments are the bait, he explains, but they have been replaced by an expanded programme of subsidised crop insurance. The CBO calculates that more than two-thirds of the $50 billion saved by cutting direct payments would be used to boost other farm programmes, such as crop insurance and disaster relief. If crop prices fall, insurance payouts will explode. And crop prices are near historic highs right now.Federal crop insurance is not new; it began in the 1930s. But its cost has already risen from $2 billion in 2001 to $7 billion last year (see chart). It is expensive because taxpayers pay two-thirds of each farmer’s premiums, and most of the claims. During last year’s drought, crop-insurance payouts were a bountiful $17 billion. Uncle Sam shouldered three-quarters of that.

Insurance already costs more than direct payments, and there is no limit to how much of it farmers may receive. The bigger the farm, the bigger the trough. (If taxpayers need insurance against misfortune, they must pay for it themselves, of course.)

Subsidised crop insurance is also bad for the environment. Craig Cox of EWG, a green pressure group, worries that it spurs farmers to take greater environmental risks, for example by farming on flood plains or steep hills. He fears that a “pumped-up” version will create even more perverse incentives.

On May 23rd an amendment sponsored by Mr Coburn, a Republican, and Richard Durbin, a Democrat, passed through the Senate. It reduces by 15% the subsidies for crop-insurance premiums if a farmer makes profits of more than $750,000 a year. Some farms currently receive more than $1m a year in subsidy. Mr Durbin says the amendment will save more than $1.1 billion over ten years—a whopping 1/875th of the total bill.

The sugar lobby fought off an attempt to remove Depression-era supports that keep sugar much more expensive in America than in the rest of the world. The industry’s sweetheart was Al Franken, a Democrat from Minnesota and the author of a book called “Lies and the Lying Liars who Tell Them”. He argued that cheap sugar would destroy American jobs. Such as those of Minnesota’s many sugar-beet growers.

The bill may face pitchforks in the House of Representatives. John Boehner, the Speaker, fumes that it takes “Soviet-style” dairy supports and makes them worse. A new scheme seeks to protect the margins of milk producers, who are grumbling that the cost of cattle feed has risen. Randy Schnepf of the Congressional Research Service wonders whether this might be because the government also encourages Americans to turn corn into ethanol and burn it in their cars.

Mr Boehner’s spokesman says the Speaker would like an open debate on the floor of the House. He expects lawmakers to tussle over crop insurance, dairy supports, food stamps and the food aid that America sends overseas.

This last point is important. Congress has traditionally decreed that such aid should be shipped from America, which costs more and ruins farmers in the poor countries that the policy is supposed to help. Mr Obama has urged lawmakers to allow food aid to be bought locally, thus saving more lives. One way of doing this would be via the farm bill, but neither draft allows it.

Original Article Here

No comments:

Post a Comment